In a recent article, we delved into the relationship between costs and sales and how knowing your gross profit margin is key to retail business growth.

That’s why inventory can be a funny thing for retailers. It’s so often one of the biggest costs, while also being the primary source of business income.

This delicate balance is why it can be helpful to better understand how to track, understand and improve inventory costing on your books. Put simply, inventory costing helps retailers estimate the value of their merchandise.

In this article, we’ll take you through the five ways to value your inventory:

- The retail inventory method

- The specific identification method

- The First In, First Out (FIFO) method

- The Last In, First Out (LIFO) method

- The weighted average method

Let’s dive in!

Inventory’s impact on retailer profitability

Before we go on, another word about inventory’s importance. It really matters. Getting an accurate picture of your inventory can be a challenge, but it’s important to do so. You need to know how much inventory you have in your business at different times, as well as product-level data about what is selling and what is stalling.

Similarly, it pays to know how much stock is being sold or lost each day, month and year through frequent cycle counting and accurate inventory management records. Having too much or too little inventory, along with discounting, can hit your bottom line if you aren’t careful.

1. The retail inventory method explained

The retail method provides the ending inventory balance for a store by measuring the cost of inventory relative to the price of the goods. In essence, it determines how much expense to recognize this period versus the next period.

The retail method assumes that all your inventory has a consistent markup, explains Abir Syed (CPA) of UpCounting. “So you take the total value of what you have for sale, reduce it by its markup, and use that number as your cost.”

The pros and cons of the retail method

The benefit of this method, explains Abir, is that it’s extremely easy to calculate and can work when you have weak inventory cost tracking. “The main con is that it’s generally not very accurate, especially if you have prices that fluctuate at different times of the year (which most retailers do), and if you have products with different markups.”

FitSmallBusiness tax and accounting analyst Tim Yoder says the retail inventory method works best if you have a standard markup, within broad product lines. “If your markups vary widely among products, then your estimate won’t be very accurate,” says Tim.

Retail inventory method formula

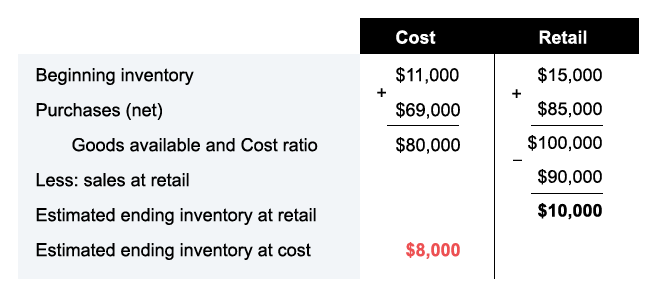

Here is the retail method formula, courtesy of AccountingCoach.

Example of the retail inventory method

As AccountingCoach explains in the above example, the cost of goods available of $80,000 is divided by the retail amount of goods available ($100,000). This results in a cost-to-retail ratio (or cost ratio) of 80%. To get the estimated ending inventory at cost, you multiply the estimated ending inventory at retail ($10,000) times the cost ratio of 80% to arrive at $8,000.

2. The specific identification method explained

Next up is the specific identification method.

This is when you assign a specific cost to each and every item in your store. Abir says this method makes the most sense for retailers that have a lot of different items, especially if they were bought from various sources. “A good example would be an antique dealer,” says Abir.

The pros and cons of the specific identification method

The pros and cons of the specific identification method depend on the size of your retail business, according to the Corporate Finance Institute (CFI). For the specific identification method to suit your retail business, you need to be able to confidently and accurately identify the location, cost, and sale amount of every stock-keeping unit (SKU) in your inventory. The bigger your business and its inventory, the harder that becomes.

The CFI suggests specific identification is better suited to small businesses because it can give them a more accurate profit and loss statement, with reliable numbers on income and losses and normal spoilage of inventory (due to things like accidental damage).

Specific identification method formula

Here is a simplified specific identification method formula, based on the following values:

- (A) Purchase quantity = 3,000

- (B) Units sold = 1,000

- (C) Balance = 2,000 (C = A – B)

- (D) Price = $5.00

- Closing inventory = $10,000 (C x D)

- Cost of Goods Sold = $5,000 (B x D)

Example of the specific identification method

“Let’s say someone sells unique paintings that they buy from local artists and then sells,” says Abir.

“This person has one painting in stock worth $150. They then buy three paintings for $100, $200, and $350. So their total cost of inventory is the sum of all the individual costs ($150 + $100 + $200 + $350 = $800).”

“If they then sell the $200 painting, their cost of inventory would be $800 – $200 = $600. Each item’s cost is tracked separately.”

3. The First In, First Out (FIFO) method

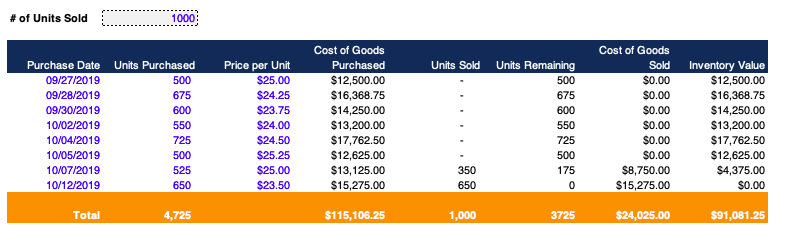

When you have large numbers of nearly identical items, specific identification may not be worth the effort. First In, First Out, or FIFO, might be better. FIFO assumes that any sale of an item is from the oldest batch on hand, and is relevant when the prices you bought it at fluctuate.

The pros and cons of the FIFO method

“This method will give you a very accurate representation of your inventory, which can be beneficial if you buy batches of the same item at varying prices,” says Abir. “It will often mirror reality as older units of a stock-keeping unit (that scannable barcode) tend to be sold before the newer ones in ideal circumstances.

“The downside is that it takes more effort to track different costs within the same stock-keeping unit for different batches of purchases. For example, if you sell a particular shirt with one universal product code (UPC) that was bought in three batches, it’s harder to track a different cost for each batch than one cost for the entire UPC.”

FIFO method formula

As Freshbooks explains, you can calculate FIFO by multiplying the cost of your oldest inventory by the amount of that inventory sold.

Example of the FIFO method

“Let’s say someone sells leather jackets,” says Abir. “They buy 10 for $100 each, and then later 10 more for $90 each. The total value of the inventory will be ($100 x 10) + ($90 x 10) = $1,900. Even if all jackets were identical and sitting on the same rack, if they were to sell three jackets, they would calculate the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) by deducting it from the older batch purchased at $100/each—regardless of which batch they were actually sold from.”

He adds: “So their ending inventory cost would be $1,900 minus (3 x $100) = $1,600. The logic here is that the more accurate inventory cost would be the more recent purchase price, as that’s the price you’re more likely to buy more inventory at.”

4. The Last In, First Out (LIFO) method

LIFO, as the name suggests, is basically the opposite of FIFO. It treats the last items bought as the first ones sold. Here’s what Abir has to say about this method.

“LIFO is when you attribute specific costs to individual items or batches of items based on their actual cost, and you reduce your cost as you sell items with the last items added being removed from inventory first. This method only makes sense when it actually mirrors reality where the newest items are sold first, and older items can sit there for a long time.”

It’s not a particularly common method, he explains, because this rarely happens in retail.

The pros and cons of the LIFO method

LIFO is definitely not for every retailer. In fact, it can only be used in the United States under the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Elsewhere, this method is not allowed by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). It can create an added burden around record-keeping. For many businesses, it’s a system that is just too complex to justify using.

That said, one of the main benefits is tax. Because LIFO results in a higher Costs of Goods Sold (COGS), the method may help rein in tax liabilities. Still, it’s always important to check the exact impacts of LIFO with your accountant or tax advisor.

LIFO method formula

Investopedia has the following helpful LIFO example, of a furniture store that buys 200 chairs for $10 per unit. Next month the store buys another 300 chairs for $20 each, and at the end of their accounting period, it has sold 100 total chairs.

Cost of goods sold = 100 chairs sold x $20 = $2,000

Remaining inventory = (200 chairs x $10) + (200 chairs x $20) = $6,000

Example of the LIFO method

Here’s a more detailed LIFO example, from the Corporate Finance Institute.

5. The weighted average method

Lastly, if the prices of the products you buy hardly change then you can use an even easier method called Weighted Average Costing.

With the weighted average method, you use a pool of cost for all units of a particular stock keeping unit. Any purchase is added to the pool of cost, and the pool of cost is divided by all units you have on hand.

The pros and cons of the weighted average method

“The benefit is that it’s much easier to track than specific costing because you don’t need to know exactly which batch a sold unit was part of, which is especially helpful when you have many identical units,” says Abir. It may also give you a more accurate costing method than the retail method—which doesn’t compensate for discounts or differing margins across SKUs.

What is the downside? This method can be less accurate than specific costing because you’re blending all your purchases together, says Abir. “But this is only a real problem if you buy a particular stock-keeping unit at very different prices each time you purchase, which is often not the case.”

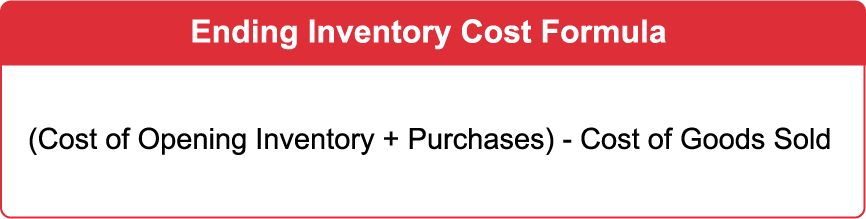

Weighted average method formula

For this method your inventory cost at the end of a period is calculated as follows:

Your unit cost is simply the total cost for a given product, divided by the total number of units you have.

Example of the weighted average method

Let’s hear an example from Abir again.

“If we used this method for our leather jacket example from the above [FIFO section], after you purchase both batches of jackets, your total cost of inventory will still be $1,900,” he says.

“The difference is that instead of having 10 jackets worth $100 each and 10 worth $90 each, you’ll have 20 jackets worth $95 ($1,900 / 20) each. And so if you sold three jackets, you wouldn’t sell $300 worth, you’d sell $95 * 3 = $285. So your ending inventory balance would be $1,900 – $285 = $1,615.”

Tax ramifications of inventory costing

As a retailer, you can track the costs of inventory purchases throughout the year. But you are not allowed to deduct the cost of inventory on hand at the end of the year. The cost of inventory on hand must be included on your ending balance sheet as an asset and deducted in the following year when your inventory is sold. Again it’s worth asking your accountant or tax agent about what each method means for your business and its tax obligations.

Retail accounting: Inventory management is key

You might have figured out by now that inventory management can be as simple or as complicated as you need to make it. One thing is clear though, it can give you a vitally important picture of the health of your business. It can help challenge your assumptions about the strength of your sales, by spotlighting the cost of your goods sold, and the time it takes you to shift different kinds of stock.

News you care about. Tips you can use.

Everything your business needs to grow, delivered straight to your inbox.